Litang (理塘)

19 June 2019.

Brief stop near Yajiang, 1101 hr. This convenience shop was the only one in the area and it was interestingly located off a bend in the highway.

The journey from Kangding to Litang took about 7 hours. No one alighted along the way, everyone was bound for Litang.

I took a deep breath upon exiting the doors of the long distance bus. I could still breathe normally. Alarm bells rang distinctly in my head though as I recall web-based warnings about spending the night at Litang’s 4000m altitude. I decided to simply take things slowly for now.

Arrival in Litang. 1411 hr. Found it amusing to witness jammed pack field packs at the exit door.

The area outside the local bus station was empty except for a few passing cars. The bus station was located at a network of highway roads leading towards Yunnan in the South, Chengdu in the East and Ganzi in the West. Most people from the bus were taking a taxi into Litang town. I followed a Tibetan man out of the bus station who hurried to board a waiting small bus across the road. The bus would take us to Litang town for 2 yuan. The bus waited for 10 minutes before driving off with three people on board, two Tibetan locals and myself. Interestingly, the Tibetan driver asked each of us where we would like to drop off in town. I didn’t remember the bus stopping at any of the allocated bus stops along the way. I was dropped off at a location fifteen minutes away by foot from my hostel, after backtracking with Chinese Amaps, I arrived at the Litang International Summer Youth hostel in the late afternoon.

Abroad the public bus to town, 1418 hr. Litang Hostel, 1504 hr.

“Did you walk here?” someone asked as I walked into the hostel. He had mid-length hair and seemed like one of those who managed the hostel. “Somewhat, I guess you could say so?” I replied in confusion. I thought about my short walk from where the bus dropped me off to the hostel, was that considered walking? Why would he even bring it up? I also found out that Yarchen Gar, a Buddhist monastery inhabited mostly by nuns a few hours from Litang which I had been hoping to visit was recently closed off to foreigners since April. That would mean replanning some aspects of my journey. I spent the rest of the afternoon resting and drinking plenty of water in fear of altitude sickness. I wanted to wake up alive the next morning. I looked around the room. The bottom bunk opposite mine was occupied by a compact backpack and two hiking sticks.

In Litang, the sun only sets around 2030 during the summer. At 2100, my roommate came sauntering in.

“Do you mind if I take my boots off?”

“No, why would I mind?”

“My feet will stink up the whole room.”

“No worries, no one has nice smelling feet after a long day.”

She wasn’t exaggerating, a sour smell did indeed fill the room some time after she took off her hiking boots. I was more engrossed in what she told me next though. She was walking all the way from Chengdu to Lhasa. It was her twentieth day into the three month journey and she was waiting for her friend to recover from an upset stomach before they set off to the next township.

“Wait, so that was what they meant by walking!” I exclaimed. I told her about the question the receptionist asked me that afternoon when I arrived. “You had a backpack so they thought you had walked.” she laughed. It was all very new to me, I knew people drove and biked to Lhasa but it was the first time I knew of someone walking the distance.

“So you climbed up Zheduo Mountain after exiting Kangding?”

“Yes.”

“But there was a tunnel! It was 5 KM long if I remember correctly.”

“Yeah I passed through it.”

“But there were no lights in the tunnel..”

“Yes, so I tried to walk as quickly as I could. I have a torchlight.”

I remember feeling the air grow thinner as bus winded up Zheduo mountain after leaving Kangding. The tunnel was dark except for orange lights spaced far and between on its stone walls. Trucks, buses and sedan cars zoomed past in a flash and I’d never imagined someone would be walking along this route. My hiker roommate herself a mother of two but looked extremely youthful. A Taiwanese backpacker previously wanted to join but dropped the idea when she realized walking to Lhasa was not possible for foreigners. The furthest foreigners could go was Batang. Any further into Tibet, foreigners would sign up for a guided tour.

Strolled along the main street in one direciton and back for the rest of the day. Fast Food Chain Belike was in Litang too. 1852 hr.

20 June 2019.

Litang’s monastery (长青春科尔寺) is nestled against the green hillside, looking picturesquely secluded below low hanging clouds. I spent the whole day walking around the grounds of the monastery. The experience of being immersed within the interiors of each shrines was highly overt. Paintings that surrounded me were intricately elaborate, designs of jewels, syllabus of Tibetan mantras and auspicious symbols (tashi dargye) decorated the pillars. In one of the shrines, a large, gilt-copper figure of the Buddha sits in the middle of the altar (chösham), easily rising to a height of twenty metres. Figures of deities (ku) are arranged across the entire interior walls of the building from eye level to the ceiling high above. Every piece of furniture within the shrine was painted with designs partially revealed under the dim lighting.

Dumpling Breakfast 0945 hr.

Sand Mandala Drawing. 1214 hr.

There was another building behind the main shrine and I entered, without realizing it was the monk’s quarters. I knew I could enter when I saw a female tourist speaking to an old monk at the door steps. “Yes yes, you’re welcome to go in,” the old monk replied. On all four sides of the courtyard were three stories of rooms where the monks stayed in. It must have been their break time as tens of red-robed young monks hung around the central courtyard. The pattering of footsteps, thuds of shutting wooden doors and conversations in Tibetan engulfed my senses. I was the only individual without a red robe and I wasn’t so sure if I should go any further. I was about to turn back when the old monk came from behind, asking if I would like a tour of the interior. The female tourist wasn’t around. Although I knew my fears might be irrational, a small part of me was fearful that I might be scammed somewhere.

Somehow, I removed my shoes and followed the lead of the old monk up wooden steps and through countless doorways with low headroom which he navigated through effortlessly whilst I tried to keep up, grimacing as wooden structure creaked under my weight. Strangely, I couldn’t even hear the monk’s footsteps. He looked back occasionally which gave me reassurance as I was starting to feel that I was intruding into a space I shouldn’t be in. We came to a landing where we climbed high enough to be just beneath the eyeline of another twenty metre high copper guilt Buddha figure. Under the steady gaze of a holy being, the old monk explained to me the practice of circumambulation. I nodded politely, for I was beginning to realize that I couldn’t exactly comprehend the old monk’s words I spoke no Tibetan and his Chinese was a little too heavily accented. Room after room we passed, some young monks passing by casted questioning looks but said nothing when they saw the old monk. Once, the old monk pushed open a door to a small brightly painted room where six other monks were seated around deep in discussion. They stood up almost at once and made a way for us to pass through to the next room. It was an unsettling feeling as I made my way across the room, there were books and paper spread over the floor and I tried not to step over them. The old monk eventually showed me to an altar at the end of one of a seemingly endless maze of dimly lit rooms. There was an image of the Dalai Lama and of two other highly revered monks whose names I never got hold of. All I knew was that I should offer respects within this sacred space. Almost suddenly, the old monk announced that he has ended his tour by and proceeded to give me a verbal blessing. I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to do in return and simply lowered my head in gratitude with an awkward “Thank you, you too.”

“Bye bye,” was his reply and without warning, I watched helplessly as he left the altar room through another door. There was no way I could follow him as I probably wasn’t allowed beyond this space. I couldn’t even ask him for a nearest exit as he was gone before I realized it. I must make my way back where I came from. I apologetically made my way through the room of six monks as two of them cleared a pathway for my passing through. Once I came to the landing under the eye of the Buddha figure, I made my way down as fast as I could, trying to backtrack my steps. A group of monks were moving furniture and were stuck at a narrow flight of stairs I was hoping to exit from. When they were done, I hurried down and heaved a sigh of relief upon sight of the courtyard. It was a lively scene, young monks paced around reading their texts out loud in Tibetan, some were carrying laundry and bowls of rice from room to room. I left the monk’s quarters soon after to return to the main shrine.

Back at the main shrine where I spent most of my time admiring the aesthetics of my painted surroundings, I couldn’t help but notice a blue jacket tourist. Apart from the fact that he was the only other being in the shrine, there was a sense of genuinity and respect within him which I found unusual. For a long time, he held his palms to his forehead in prayer. He was fair skinned, wore black framed spectacles and had a DSLR around his neck. I later saw him again at another three shrines. He took care to observe as much detail as he could, feeling the space rather than simply clicking away at the camera. It was almost like a fairytale experience to share such sacred spaces with another solo traveller in silence and whilst I longed to approach him to ask more, some things are better left wordless.

Having explored the monastery grounds grounds, I decided to walk around the shrine this time. There was an uphill dirt path which I had never seen before and it led me to a grassy plain where I could see a panoramic view of Litang Town. There were monks sitting in circles on the grass and grazing yaks further in the distance.

“Come sit with us” one of the monks called out from a distance away as I cut through the field to see the town view.

I was taken aback. From what little I knew, monks would never call out like that, especially to females as we were always supposed to keep a distance away from the monks. Yet, the Buddhist practice back in Southeast Asia differs greatly from the one here in China and I wondered if the monks followed similar traditions.

The monk who called out was seated with three other monks. They were dressed in red robes and looked like they were teenagers themselves. One of them carried an umbrella over his head and as I approached them, I realised he had shades on. I sat down on the grass a little away from them and there was silence for the longest time possible. They spoke amongst themselves in Tibetan.

“Are you feeling breathless?” the monk who called out to me asked, attempting to break the silence.

I nodded, thinking of how to continue the conversation. Surely it was awkward for all of us. It was 1400 and I had nothing planned for the afternoon. I had to strike a conversation.

One of the monks was fiddling with a tiny can of brown substance and I decided to start with that. I shifted myself closer to them and begin to ask about it. It was a powdery brown substance and they weren’t going to tell me what it was, all I deduced from them was that it wasn’t edible. I soon found out they were indeed young monks, the youngest amongst the four was 16, the eldest was 22. The young monk who called out to me was actively conversed with me in Chinese whilst the other three spoke amongst themselves in Tibetan which was natural as I was a complete stranger who had simply sat down beside them. He shared that Tibetans believed in reporting a number one year older than their actual age thus, they were around 15 to 21. Bit by bit, he started sharing about his life as a monk. Three of them had joined the monastery after attending middle school whilst the youngest of them joined the monastery when he was six years of age.

It was their afternoon break and the four friends were simply chilling out in the open. They had another friend who would usually hang out with them but for today, he was somewhere in the monastery. Their afternoon break was rather long, from 1330 to 1700 where they would have their dinner and continue their studies till 2100 at night. Sunday was their rest day where they would either head to town with friends or back home to their families. Two of the young monks were from Litang Town themselves whilst the other two were from 君坝乡Jun4 Ba1 Xiang, half an hour from Litang Town. The other three monks began to chip in.

1611 hr.

“We have to study for 15 years”

“Yes, by the time we graduate we would already be in our thirties”

“What happens after you graduate?”

“We will be gexis”

“How should I address you all then?”

“We are ahkes.”

“How do I differentiate between an ahke and gexi?”

“Gexis wear yellow.”

“Are they gexis?” I asked, referring to a group of three monks with yellow caps on their heads in the distance.

“No, they are ahkes like us.”

“But they have yellow hats.”

The young monks thought for a while. I was asking the obvious but they remained patient with my ignorance.

“We can wear those too.” one of them replied.

Ahkes (啊可) can be identified by their red robes whilst gexis (格西) would wear a shawl with dinstinct yellow at their front and back. The headgear is also different, ahkes would wear yellow lotus like caps whilst gexis wear high hats shaped like a rooster’s comb.

The young monks were effectively bilingual, speaking error-free Chinese without the TIbetan accent. Monkhood was their personal choice and like most people I have met in Tibet, they were candid, straightforward in their speech and their eyes spoke volumes.

“Did you know, we females usually are not allowed to have direct contact with monks?”

“Really?” they looked at each other in alarm and started to inch away from me.

“Yes.” I laughed. “So I was really surprised when you called out to me just now.”

“It’s alright for us.”

“I guess it’s a little different here.”

I stared down at a pile of yak dung in front of me.

“It’s dry. Touch it.” One of the young monks reached forward to flip open the dried tip of the dung. The inside was a wet murky dark brown, congregated with flies. The smell wasn’t anything of concern though, it was easily masked by natural earthy scent of the lush green grass fields.

“Did you know you can become whiter if you rub yak dung over your face?”

“Seriously?

“He does that!” the monks pointed towards that young monk who had initially called out to me. He was certainly fairer than the rest and was laughing hysterically. The conversation soon started to become friendlier as they joked about one another.

“He has a race horse.” one of the monks pointed to another.

“I’ve two.” The other monk showed me a phone photo of a handsome white horse adorned with colourful laces and flags. His family had bought the race horse for 80,000 yuan, I almost gasped when I heard the price.

“We have an annual horse racing festival in Litang every August.”

“Oh yes I just read about it!”

I showed them the guide book I got from the hostel earlier. It was in English thus they mainly looked at the images.

“Have you been to the House of the 7th Dalai Lama?” one monk pointed to an image in the guidebook.

“Wait, did you know he is a descendant of the 7th Dalai Lama?” another monk piped, pointing to the monk in shades.

“He looks like it.” I replied. Monks usually only speak the truth but again, I took everything with a pinch of salt.

“His brother guards the House of the 7th Dalai Lama at Renkang Ancient Street.”

“Yeah my brother, the watchdog.” the monk with shades joked.

“Does he look like you?”

“Not at all. You’ll know when you visit the House of the 7th Dalai Lama.”

As I heard more from them, the lifestyles of the young monks didn’t seem as secluded and solemn as I had thought them to be. They posted selfies, sceneries and updates about their everyday lives like any young adult. Studies at the monastery was almost like University, they had subject specializations in debate, written and scripture memorization and sat for yearly exams. These four monks had good dispositions and are morally grounded, honest individuals who like many of us, are trying to commit to the tough journey ahead.

Sometime later, the group of three monks with yellow caps who were seated in the distance came by and spoke to the young monks in Tibetan. They looked a little older, but were definitely still in their early twenties. After they left, the young monks told me they didn’t speak Chinese as they never went to school. “They’re herders.” one of them explained.

“Tibetan seems difficult.”

“Yes, its harder to learn Tibetan than Chinese.” One of the monks had his study book with him which I took a look at to admire the neatly written Tibetan script. Another turned on music on his phone. The Tibetan song he was playing had a catchy tune.

Anu is a Tibetan band of two from China’s Qinghai province whose songs would stay on my playlist in the coming months. “Do they have passports then?” I asked, aware that minority groups in China do not have passports.

“I’m not sure if they are famous enough to apply for one. But for us, we don’t have passports.”

Sometime later, the conversation took a more solemn turn after I mentioned that I was intending to witness a sky burial. These four monks had already seen them and they made known their firm belief in the existence of the supernatural.

“Not everyone in Litang gets a sky burial. Some are buried.” they pointed to a cluster of tall trees. At 4000m, Litang had very few trees and only a line of them stood in the far distance amongst the rolling hills. “The ground burial site is right where the cluster of trees are. The sky burial site is on the hills behind that cluster of trees.”

“I heard it’s just outside town. It doesn’t look too far away.”

“There are countless souls at the sky burial site.”

“We monks will never tell a lie.”

“Don’t take photos of the body when you are there.” the young monk with shades advised.

“Yes, I’ve heard about that. How about the vultures?”

“You can take photos of the vultures. But not the body, it’s disrespectful.”

“What happens if I do?”

“Then you’ll be the next one.”

1804 hr.

Really like this quote I saw within the City. 2002 hr. It is an affirmation of determination that appeals to local circumstances, in direct translation:

“A lack of oxygen does not equate to a lack of energy/ spirit. We may live harsh lives but we aren’t afraid of hard work.

Dinner. 2031 hr. The potato strips do indeed vary in colour and taste from province to province.

My roommate for this day was a friendly Chinese lady from Beijing. She was previously at Yading which was my next destination. I told her about my plan to stay at Yading village and she recommended Shangrila instead. “Isn’t Shangrila in Yunnan?” I asked, horrified. For a moment, I thought I had gone wrong in my planning. “Nono, there was a small Shangrila town outside Yading. Most people will opt to stay there rather than Yading Village which is more expensive.” she explained.

She left an important advice I was most glad to heed later in Yading. Head for the Five Colours Lake first, no matter how arduous the climb looks to be.

21 June 2019. (Sky Burial དུར་ཁྲོད།)

I woke up at 0600 that Friday morning. The first cab I flagged down asked me for 30 yuan to the burial site. I decided to flag down a second cab, only to meet with a similar request. In Litang, every cab charges a flat fare for destinations outside town in the morning.

The burial site wasn’t too far outside town. It was in the hills and as the cab turned from the main road onto the muddy tracks, I couldn’t help noticing how barren the surroundings were. The soil was damp and hard, with grass growing in clumps. This was probably the only area where I could not spot any yak dung for miles around. I could only hear the raging wind blowing at a mast of colourful prayer flags beside the burial site. In the distance towards the east, I could see the cluster of tall trees the four young monks referred to yesterday. I must then be in the west, and from where I was, I could not even see the shrine.

The cab dropped me off at the foot of the hills. There was a car parked at the site, in it was a Tibetan man whose purpose there I never dared to ask. A small white building stood at the burial site. It was locked and its windows were too high up for me to pull myself up. There was also a stone altar to offer incense at and another stone structure which looked to be for burning offerings. Shifting my glance towards the hilly slopes, I caught my first sight of black vultures circling in the sky.

As I climbed up the gentle slopes of the hill, I was thrown into deep thought. There was a pile of stones with mantras carved onto the surface. The carcass of a cow lay on the ground, with nothing left of it except its skeleton and hide. A pair of scissors, two axes scattered on the ground. Following them, I came to a flat landing on the hill. There was no grass growing here, instead there were tools lying around against heavy stones. Looking towards the foot of the hill, a foreigner had joined me at the burial site. He had arrived by bicycle and was standing around. We were early probably because we heard that the process would start at 0730.

The crowd at the foot of the hill grew bigger. Three Chinese and a foreigner came in an SUV. Another two foreigners later arrived, each by themselves. It was a little after 0730, the surroundings were exceedingly cold and I kept on walking to distract myself. By 0800, the Tibetan man and the three Chinese drove away. We had waited for an hour and no one had approached the burial site except for the group of us. At 0830, I decided to leave the burial site as the cold was becoming unbearable. On the bright side, I was relieved no one came to the site for it implied that no one died in the recent days. The foreigners were still waiting at the foot of the hill. I gradually made my way out of the burial site, stretching my neck to spot any oncoming cars from the main road. Almost suddenly, a car turned in from the main road. I backtracked cautiously, the car stopped in front of the mast of prayer flags. Two Tibetan men exited the vehicle to hang up new prayer flags before driving towards the waiting foreigners. They spoke a bit before leaving to climb the hill, I approached the foreigners. Apparently, they had conversed with the Tibetan men with Google translate but the attempt wasn’t effective.

“Do you speak Chinese? Maybe you could ask them if there is a body today.” they asked me. I was curious too, and went to ask. The two Tibetan men weren’t sure too, they had come to put up prayer flags for their relative. The foreigners were going to wait it out. “My friend waited till 1130 when he was here. I’m just going to hang around.” one of them said. Soon, a black SUV joined us. Two Chinese emerged from its doors. They were from Litang themselves but were intending to observe the sky burial for the first time. Since they were all staying put, I too decided to wait it out. “There’s a body inside.” one of the foreigners informed, pointing to the white building.

The two Chinese men swung themselves up the window steel bars to take a look. They described the body to be covered in white sheet, with both feet sticking out. With the body present, the foreigners were convinced that the procedure would occur that day. The two Chinese weren’t so sure about it but we were going to wait it out with small talk. Interestingly, the four foreigners were from Israel. They arrived separately though, without knowing one another beforehand. One of them was going to hitchhike to Shangrila and asked if I would like to come along. We soon realized that we were looking at different two different Shangrilas. “I’m going to the big Shangrila. The one you are going to is the small Shangrila.” he replied. It took me some time to figure it out. The Shangrila he was going to was a city in Yunnan, whilst the one in Sichuan’s Yading was a small Shangrila Town. A vehicle pulled up beside us at 0930. This time, it was a group of Tibetan men. They dragged two large sacks from their vehicle and started busying themselves around the altar. One of them unloaded a pile of personal belongings into the stone furnace. Heaps of clothes, a watch, unfinished yogurt and apples came pouring out from the sacks. What we were waited hours for was now happening right in front of our eyes but I felt a dull ache, someone will be going through the pain.

The three Chinese drove to the site soon after. One of the Israelis had their Wechat contact as they had previously offered him a ride from Yading to Litang. The Tibetan men started boiling a pot of substance with a self-made fire. It was for the bones, though I wasn’t exactly sure in what way. They carried a white body bag up the hill to the flat landing. We respectfully stayed behind at the foot of the hill until they gave us the green light to approach them.

From afar, we could still see what was going on. The group of about ten Tibetan men closed in on the bare male corpse, splitting up the stomach area with a knife. As they closed in further to work on the body, the onlooking vultures were already gathered next to them and more were rapidly descending from the high skies.

Once the Tibetans who held the birds back backed off, the vultures caved in on the body almost immediately. The Tibetans gestured for us to approach them. We gestured, silently asking if they were alright with the presence of our cameras. To our surprise, they nodded. The vultures jumped on top of one another in a frenzy. A few vultures squeezed out from the flock with bloodied heads, one of the vultures had a with a piece of purplish flesh hanging from the curved tip of its beak. We saw nothing of the body as the swarm of birds feasted a metre away from us, dead silence enveloped us amidst the constant flapping of wings and the guttural screeches of the vultures.

The Tibetan men moved in after some time and the vultures gradually backed off. The body laid on its back, skeletonized clean by the vultures. It wasn’t at all white, but a brownish red hue from the dried up blood. There was nothing left of the flesh.Three vultures were still picking away at the bones. There was no blood though.

We stayed extremely still and silent. No one clicked at their cameras. We couldn’t do it. I had promised myself that I was only going to take videos of the vultures, not the body. The body on the ground was no different from my own, just that I was still alive and breathing. My helpless skeleton would also pass off an acrid stench and look like a bloodied mess and I wouldn’t want tourists gawking and pinching their noses at the sight of my lifeless body. I didn’t move for the longest time as I watched some of the Tibetan men close in on the skeletal body, lifting large stone slabs with their gloved hands. Two of them swung their jackets, prancing around the area to scare the vultures away from the body. “My brother.” one of the Tibetan men spoke as he passed by. I didn’t know how to respond. “Om mane padme hum..” was my weak attempt at a reply. He nodded slowly, looking away.

The men started to break the skeleton apart at its joints. The leg bone was broken into two at the knee cap and thigh bone twisted away from the pelvis. The arm bones were separated from the shoulder and one of the men held down the spine, twisting every rib bone with his gloved hands until the rib cage was gone. I didn’t know our bones were so fragile. A few of them started to ground these bones against the stone slabs they had carried over. Another detached the skull from the neck and worked at dislocating the jaw bone. He later broke open the skull with a stone. We watched the skeleton turn into a pile of greyish red mixture. It was almost like powder. In those two hours, the vultures closed in on us every now and then.

The two Litang Chinese locals left the scene at this point. They politely asked if I needed a ride back to town which I declined as I was not intending to leave just yet. One of the Tibetan men started to brush away at the jacket of a Chinese tourist. Some of the powder had dissipated in the winds and had settled onto his jacket. Apparently, I had some on myself too as the Tibetan man later approached me. I couldn’t spot anything on my black jacket but I figured that but this time, it would probably already be in my hair, jacket and trapped amongst the threads of my bag. I wasn’t prepared for this but it seemed pointless to brush off powder-like substances blown about in the never ceeding gust of wind.

As the men worked on the bones, I realized the vultures scurried away as I approached. They were massive creatures, rising to above my hip level. With powerful claws and hard beaks that reflected the morning light, I was bewildered by the irony that they were afraid of the living but would readily pounce upon the dead. With the vultures scrambling away from my path with my every step, I begin to realize how noble the practice was. Death occurs to everyone and I couldn’t yet stomach the idea of offering myself as food. The sight of the vultures swarming over the body, their glistening sharp beaks tearing at the flesh was too visibly painful to bear. The dead may feel no pain but the living did, simply by watching. I was baffled that some of the Tibetan men who managed the body were brothers of the deceased. The rest were villagers and although I heard there was a priest/ body breaker, I never got to identify him amongst them.

I recorded a video of a Tibetan man with a yellow jacket who jumped around, flapping his jacket at the vultures to keep them away from the skeletal body. He later approached to ask if he could watch the video I recorded of him. I played the clip and he began asking me about the price of my camera. Within minutes a small crowd of Tibetans gathered around me, interested in exploring the functions of my camera. They didn’t mention it outrightl though. I showed them the basic functions and left them my camera to explore. The sky burial practice is often a private affair and I wanted to make up for my intrusive presence as best as I could.

As they tried out my camera, I took a good look around me. A small fleet of SUVs have since gathered at the foot of the hill and a large family of women sat around them. They were chanting with the prayer beads in hand as flames of a fire burned into the skies. The belongings of the deceased were already engulfed in the orange flames, ascend to the heavens along with him. When the bones have been pounded into fine powder, the men mixed it with tsampa to form two piles of grey mixture on the ground. The vultures crowded in and the fight started once again when the Tibetan men backed off. Our bodies, complete with the finest details of hair and pores is ultimately a pile of grey powder like substance.

After the last remains were fed to the vultures, they soared back up into the skies, circling around with their majestic wingspans. I felt for my physically intact flesh, knowing that the body once had what I currently have. My body is nothing more than a reduced pile of grey mixture but I will treasure it for the appearance and mobility it gives me.

The three Chinese gave myself and one of the Israeli tourists a ride back to town. Once in town, we came to some barricades, blue-uniformed policemen and an enormous crowd at a small road intersection. All vehicles stopped for some time for them to pass through. They were celebrating a marriage, a Tibetan bride downed in red was ushered by the crowd into the town’s community centre. We wanted to get down to observe the wedding but didn’t do so in the end as we had just came back from a sky burial. We later heeded to Medok’s Inn where the three Chinese and the Israeli tourist were staying for 30RMB per night. I had to take a look as the only international hostel option I knew of in Litang was the current Litang Summer International Youth Hostel I was staying at. A Chinese man from Sichuan greeted us as we walked through the doors, recognizing me by my black jacket. He was the boss of his hostel and had driven his guests to the foot of the sky burial site earlier that morning when I was walking around the hills to keep myself warm. The dormitory rooms looked comfortable, the three Chinese and one Israeli tourists occupied one big room with around eleven beds spread out across the length of the room. Unfortunately, I had already paid for my night’s stay at Litang Summer and couldn’t change my hostel that night. It was nearly noon and the Israeli tourist started packing up in hope to get a hitchhike to Yunnan’s Shangrila later that afternoon. I decided to go to the bus station to get a ticket to my next destination since Medok’s Inn was located halfway between Litang town and bus station.

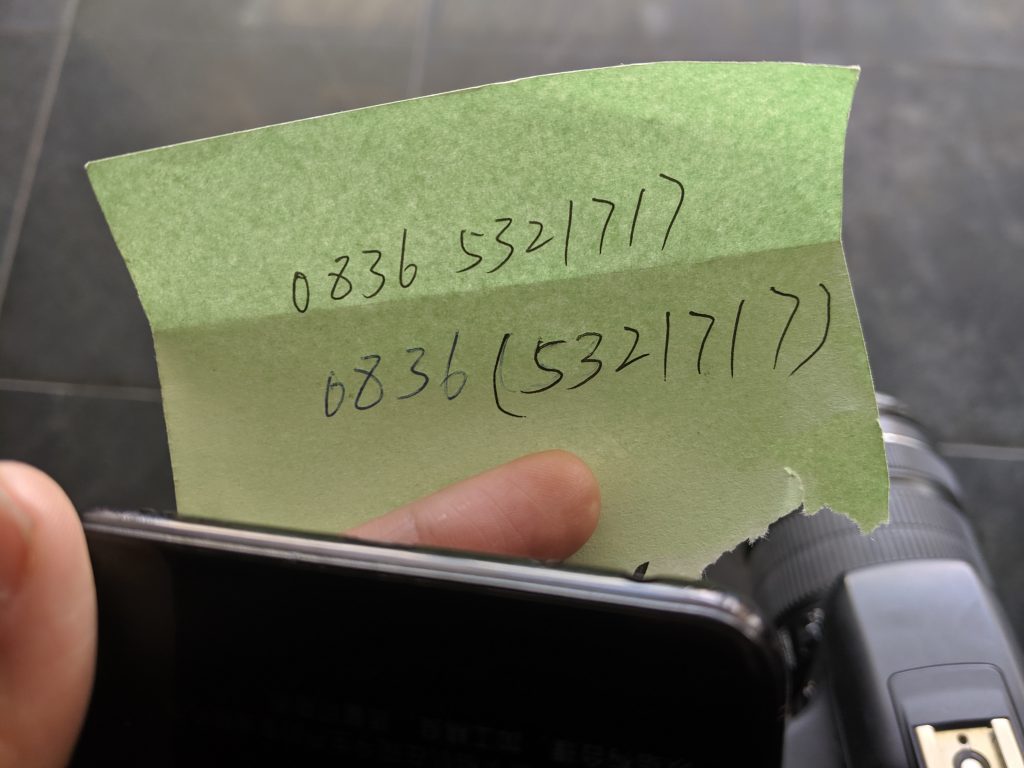

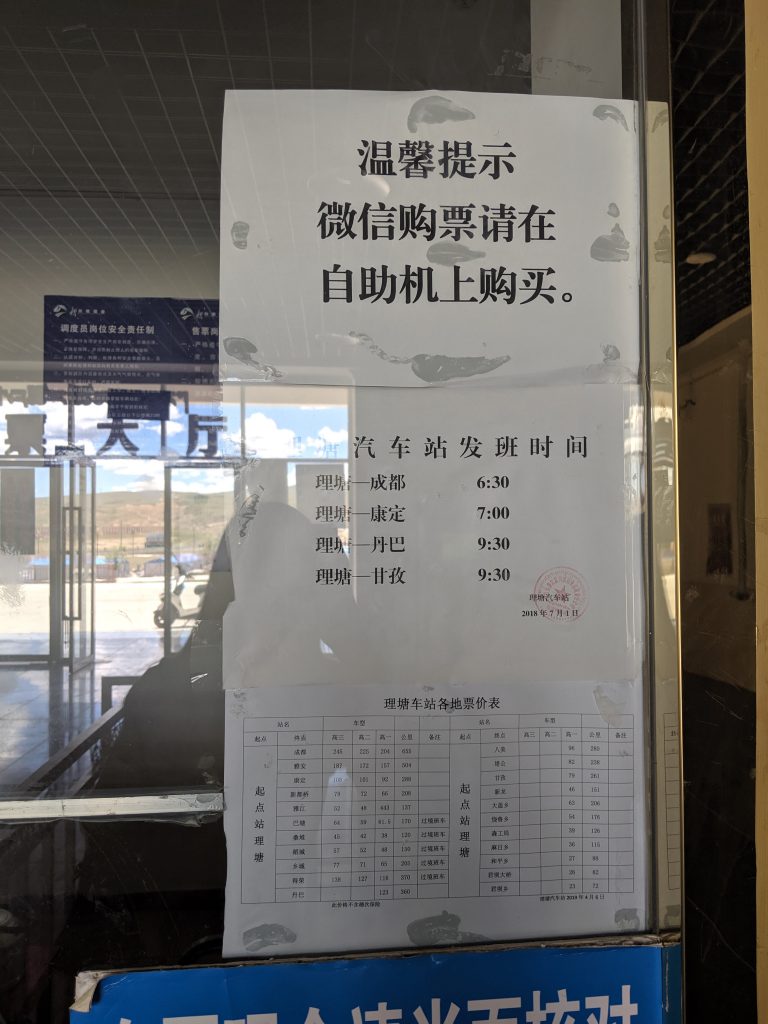

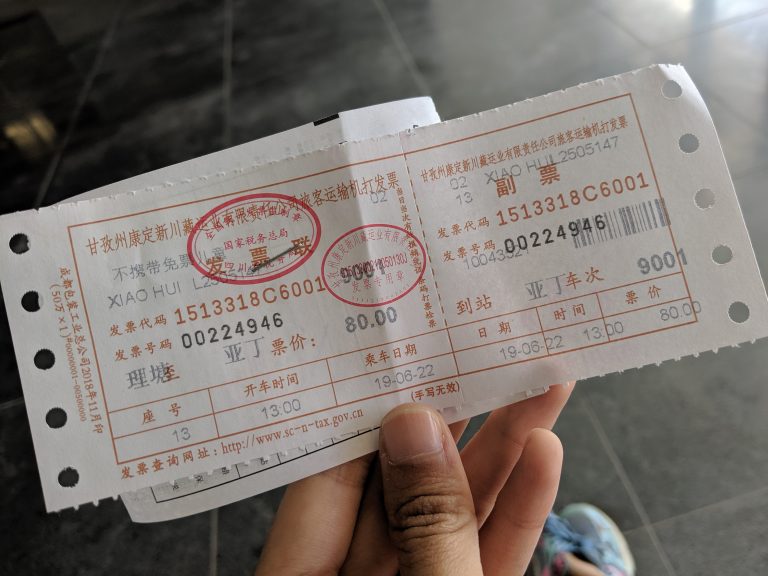

The sun was blazing hot as I climbed up the hill to the bus station. The heat was strange, it was hot but not humid enough to make one sweat and following the example of the locals I saw in town, I resisted the temptation to take off my jacket. Trudging up to the top of the hill, I was glad I made the effort to come to buy the ticket in advance as the ticket lady told me that she couldn’t get me a ticket to Yading on the spot. The bus to Yading came from Kangding and would stopover at Litang for lunch. As they weren’t yet sure of the number of passengers boarding the bus at Kangding, they could only confirm the availability of seats for me on the bus tomorrow morning. She gave me her phone number, instructing me to call her the next morning.

Bus Station. 1233 hr.

Outside the bus station, there was no sight of the small public bus which had brought me to town when I first arrived. I thought about walking down the hill back to town in the scorching heat. It would take me an hour to walk back to my hostel from the bus station. I decided to take a cab instead. There was no designated queue for cabs at the bus station, the only way I could flag one down was when a passenger alights from one at the bus statiion. However, in the half an hour I hung around, no one came to the near empty bus station. I went into the bus station and asked around, hoping to meet someone who would be a cab driver who was waiting for passengers. A Tibetan man replied that he would drive me to town, but at a later time as he had to collect his parcel. I replied that I would go out and wait around. If there was no cab coming to the bus station, there should be cabs coming from the direction of other cities at the intersection outside the bus station. I wasn’t so sure about going with the Tiibetan man after all and resorted to finding a cab on the road.

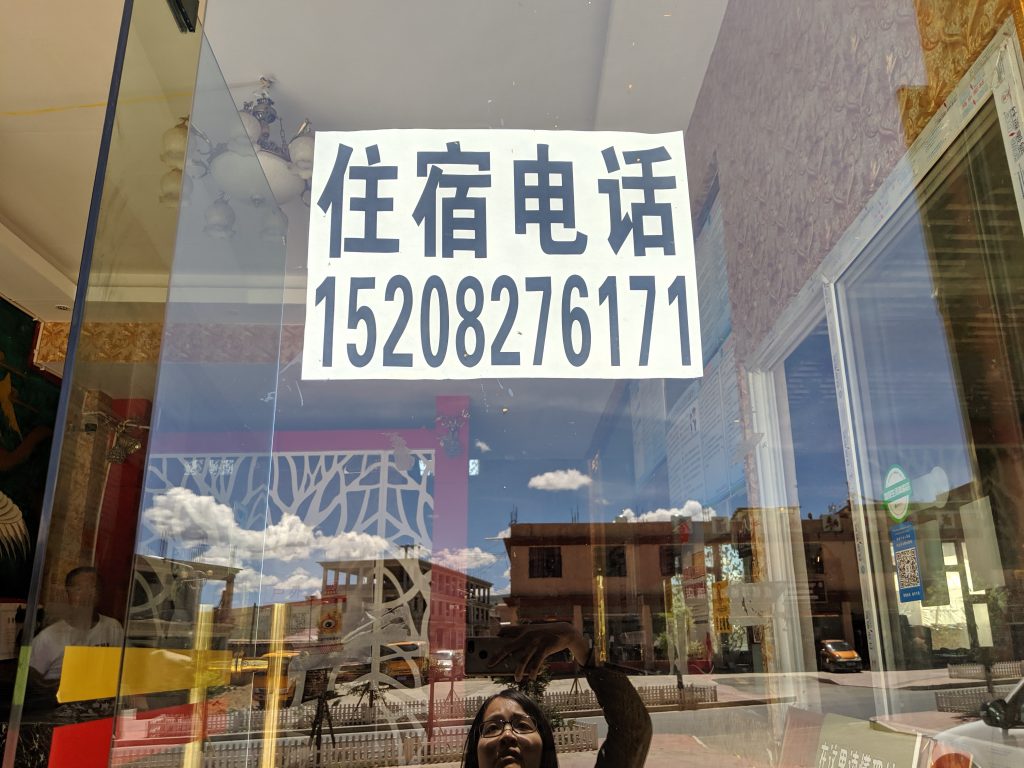

A hotel just outside the Bus Station. Similar to Kangding, the Bus Station is not located within the City Centre.

Out of the bus station, I took the road towards the intersection. At least a cab drove past me every ten minutes yet, none of them stopped. They all had passengers in them. After some time, I returned to the bus station. It was already half past one in the afternoon and I decided I had no choice but to either wait for a cab to drop someone off at the bus station or wait for clouds to envelope the burning sun. A car honked at me as I walked along the outer fringes of the bus station. “There you are!” It was the Tibetan man whom I had earlier asked if he was going to town. He wasn’t a cab driver but he was driving to town. I thought twice about getting in.

I knew where I went wrong. I intended to ask for a cab driver however, I went around the bus station asking if anyone was going to town. This Tibetan man was generous enough to offer me a lift and I wondered if I could trust him. I have long heard that such incidences were common and had a few seconds to make up my mind. I asked if he could take me to Litang town for 10 yuan to which he refused, citing that he would do so for free. That was what that was causing me to be uneasy. I insisted a few times and he finally nodded and I got into the front seat. He was from Litang but lived in Chengdu. Every two months, he would come back to his hometown and that day, he was waiting for a parcel. They didn’t have postage service in Litang, one has to wait for their mail at the bus station. He took the parcel and stopped by a shop to deliver it. “I’m going to pass it to my friend,” he said. The shop was closed though, its shutters shut tightly to the ground. He made a phonecall, his friend was away that day. With a sigh, he drove off and I knew I was safe when he told me he will drop me off at a place of his convenience. He was sincere about offering me a ride back to town since it was on the way for him and he wouldn’t go out of the way to accommodate me by driving me all the way back to my hostel. That was normal and I felt more at ease when I heard that. I dropped off at a main street and handed him 10 yuan. He refused it twice and thrice again and I returned to my hostel, thinking how generous he was.

I visited Renkang twice, once in the late evening after talking to the four monks and another in the late afternoon after the sky burial and marriage event.

I left my hostel again at mid afternoon after returning from the sky burial site. I had seen a marriage ceremony somewhere around town on the way back and since I have washed myself after witnessing the sky burial, I wondered if I could see the procession. I asked for directions, interestingly the hostel manager told me that there was no wedding that day and the next one will be held a month later on 28 July. I went into a local pharmacy to buy a bottle of 酒精 as advised by the three Chinese to clean the insides of my camera and asked about the day’s wedding. They said there was one in the morning but did not know where it was. They told me to try the town community centers which there were at least two or three. With a bit of luck, I managed to locate the building I had seen the bride entering that morning with the Chinese Amaps.

The procession was already over and five to six middle aged Tibetan women dancing around on the floor of the building. There were unopened bottles of sprite and coke as well as peanuts on the low tables. One of the Tibetan women offered me a peanut, a gesture which prompted me to enter the building. I wondered where everyone was when the ladies pointed upstairs. An eldery Tibetan couple greeted me at the top. They must have been the parents of the newlyweds. Behind them, more than a hundred guests were having an afternoon feast in around five separate dining rooms. Everyone was dressed to the nines and looked amazing. I simply hung about the corridor, unsure where to go. It was quite clear that I was the only Chinese and knew no one. A Tibetan man approached, inviting me into their dining room. “You looked lost.” he commented. Everyone in that particular dining room was male and Tibetan. I sat gingerly at the edge, thinking of an excuse to leave as I was clearly out of place. I wasn’t sure whom I was talking to, all I knew was that the women and children were in the other dining rooms. The Tibetan man who invited me in eased me into conversation with his flawless Chinese. He knew a thing or two about Singapore which was rather unusual. I could tell he wasn’t the ordinary local. I heaved a sigh of relief as the attention turned to the bride and groom who later entered the dining room for a toast. The Tibetan man poured me a glass of water to toast them. “I thought all toast beer,” I asked, looking at the glasses of beer everyone in the room held. “ We do, but you don’t drink, do you?” he responded. The newlyweds politely smiled, held their glasses to their lips and drank up in response to my awkward Chinese blessings. As they leave to make a toast to other relatives in the other rooms, I took the chance to follow them. As the newlyweds went around the different rooms, I was most impressed by the Tibetan kitchen. Its walls were black from the soot generated by preparing food from a traditional charcoal stove that sized up to a quarter of the kitchen. A family of twelve feasted in the kitchen on low benches covered with thick hand woven rugs, they took pride in the fact that they will be served each new dish first.

Crashing a Tibetan Wedding Ceremony. 1515 hr.

Outside the community centre, two Chinese policemen sat waiting in their car. Everything had quietened down since that morning and they were probably on guard till the feast ends in the early evening.

The printed guide book I retrieved from my hostel described Renkang Ancient Street as a “peaceful pub to rest, have a drink and wait for an encounter.” I had already grown to love every moment of my time in Litang and there was only going to be more surprise encounters.

Renkang Ancient Street (仁康古街) was a residential alley built in the 16th century. Back then, there were only three families living along the street, one of them the notable Renkang, a substantially influential family whose name lived on till this day. Kyelsang Gyatso, the 7th Dalai Lama was born in the Renkang House on this very street. Litang, like other Tibetan regions is blessed with an abundance of natural beauty, the Renkang Ancient Street was beautifully lined with flowering grass and dried mud brick traditional khampa houses. There was an entry sign to the Litang Folk Museum outside one of the houses and I pushed open the unlocked wooden door to enter the front yard. A Tibetan mother and grandmother were in the midst of disciplining a toddler. They stopped and smiled as I entered. There was an elephant toy on the ground which I picked up and passed over to the child. The child threw it on the ground and I tried again. When he finally accepted it, I looked towards the house and asked how I should enter the Museum. “It’s next door,” the Tibetan mother replied. “Next door? I thought – I’m sorry” I apologised profusely. What mattered more was that I had trespassed and the two Tibetan women had been so accommodating at my unintended act of rudeness that I did not even realize my mistake. Most people would have screamed, let alone smile if some stranger pushed through the front door. I took another good look at the sign outside the house. It stated that it was the folk museum but there were no directional signs. The museum was just next door and looked exactly like all the other khampa houses, except for a metal carving beside its front door, designating it as the Litang Folk Museum. Two young Chinese adults were painting black shadows on the carving, giving it a 3D effect. One of them showed me the before and after on his phone, asking if the resulting effect would look better. He had photoshopped the after and they were going to achieve the look by 7PM that day.

The museum was free entry but we needed to register before entering. Two Tibetan teenagers were playfully fighting off one another when the teenage girl approached me to get the teenage boy to stop bullying her. She later turned out to be my museum guide. “That was my cousin,” she explained as we walked to the exhibits. “He guards the Renkang House, if you are going there later you can let me know and I will get him to open the door.”

“You mean, the doors to the Renkang House are not always open?” I asked. Surely there would be hordes of tourists as the Renkang House was the birthplace of the 7th Dalai Lama.

“Nope, he’s lazy sometimes.” she laughed. I was impressed by her Chinese. She was still a High School student and was volunteering her time bringing tourists around the Museum.

The Litang Folk Museum was designed in the layout of a traditional Tibetan home, exhibiting costumes, farming and herding tools. There were wax figures all around, each frozen in the midst of performing an action.

Wax figures within the Folk Museum. 1645 hr.

Referring to the headdress of the wax figure bride, my guide explained that newlyweds I had seen earlier was not from town. Every area would have their own marriage customs and brides from Litang town would down a headdress. The bride I saw earlier had to be from one of Litang’s 19 neighbouring districts. Moving on to the exhibit of the Tibetan kitchen, she explained that they would kill all the animals they rear and store their meat for the winter, except for the females because they produced milk/ lay eggs and give birth. With my guide’s permission, I tasted tsampa at the museum where they had it as an exhibit. It wasn’t exactly a memorable taste. My teenage guide looked at her phone, “Did you know that the Bhutanese Princess is coming?” she almost bursted out. “My cousin told me!”

“What? When?” I couldn’t believe my ears.

“This evening!” she exclaimed.

The Princess would be coming in approximately an hour and a half. I was puzzled about the purpose of the royal trip though. It had to do with family lineage. I headed off to the Renkang House next as planned. My teenage guide reminded me to return to the Folk Museum and look for her if the Renkang House was closed. I passed poems carved onto the walls along the way. Some eldery Tibetans circumambulated the area and I stopped to play with a toddler who had an interest in throwing roadside stones under the supervision of his mother.

There was indeed no one in the Renkang House. The door to the front yard was open but the door to the building within was locked. I walked around and soon, a teenage boy of about fourteen joined me. He didn’t speak Chinese, I guessed he was also looking to enter the Renkang House to pay respects. I dialed a phone number pasted on the door and the keeper picked up. He came soon after, a thin and fair spunky Tibetan guy with piercings and longer than average hair tied up in a short ponytail who had “bullied” my teenage guide earlier.

“Are you going into the house?” he asked.

“Of course.” I replied.

“How about we wait for the Princess’ arrival? We can go in together.” he suggested. I nodded. I didn’t mind waiting, everything was new to me and I had a lot of questions. After exchanging a bit of background info, the keeper casually mentioned that the Renkang Family were his ancestors.

“I talked to a group of monks yesterday and one of them mentioned the exact same thing..” I replied, recalling the conversation the day before.

I was met with a prolonged silence as he eyed me with raised eyebrows.

“Was the monk fat?” he asked.

“He was chubby.” I didn’t deny that. “He’s extremely funny though.” I gushed, trying to make up for what I had said.

He took out his phone and began scrolling. “Is this the monk you met?” he asked, showing me a photo.

“Yes, it’s him!” There was no mistaking the shades he wore.

“That’s my youngest brother.”

“Oh my!” I gasped, suddenly recalling that the young monk had mentioned that his brother worked at the Renkang House. I couldn’t think of what to say and began asking the older brother how living as a descendant of the 7th Dalai Lama felt like. Their status was well-recognized in town for towns folk will address them with a formal particle whenever they exchanged conversation.

An eldery Tibetan monk and nun came through the doors of the front yard with a little girl who looked to be around three years of age. Almost immediately, the keeper sprang to his feet, unlocked the door to let them into the house. He personally brought them around, myself and the fourteen year old Tibetan teenager tailing behind. Every now and then, they bowed down to the relics.

“That’s the Han way of praying.” the keeper picked out as I bowed after them.

“I don’t know how else to do it.” I replied.

Palms to the forehead to rid oneself of harmful thoughts, lips to ensure truthful speech and then the heart to remind oneself of honesty genuinity and bow down with your forehead to the ground, he taught. “We also have a long prostration which is too long for you.” he said, referring to the postrations the Tibetans do on pilgrimage to Lhasa.

The monk stopped at almost every relic to donate 1 yuan bills. I was most intrigued by the teenage boy who took those 1 yuan bills after praying to each relic and deposited them at another relic. He took care to stay at the back, no one talked to him throughout. He simply nodded when I tried the only Tibetan word I knew, Tashi Delek. Before leaving, the monk and nun stopped by a thangka painting. For half an hour, the voice of the keeper droned on as he explained different parts of the Thangka in Tibetan, an experience I could never forget. The teenage boy listened intently from the back. The three year old girl stood motionless throughout, I had no doubt she understood what was going on.

1744 hr.

“Come, I’ll explain a bit about Litang.” the keeper said to me, locking the door after our little tour group left. I laughed. It seemed plausible that he didn’t want to go through the lengthy explanations he had to do in the house but had to do so just now out of respect for the revered monk and nun. It could also be that he saw that I knew nothing about Litang decidedly thought of showing me around Renkang Ancient Street but whatever the reason, I agreed.

Pointing out black painted windows of the Renkang House, he explained that only holy places would have their windows painted in a trapezium shape. I felt embarrassed that I had to ask about the difference between a Dalai and Lama. He was patient nonetheless, explaining his faith and family structure. I asked if the Bhutanese Princess spoke Tibetan. No was his answer. He replied that his uncle will be there to do the translation. What surprised me most was that the Bhutanese Royal Family spoke English. The Princess herself arrived on site at 1830 with three male family members and one teenage girl. About ten other Chinese and Tibetan delegates followed them. The Bhutanese royals were indeed good looking. Clothed in western style casual wear, they had beautifully tanned skin and spoke in distinctive British accents. The Princess herself was a beautiful slim lady who looked active and graceful at the same time. I followed behind as they toured the area, astonished that I would be the one who understood their conversation more than anyone else. Part of the entourage consisted of a monk in red who smiled warmly.

“Hello,” he started off.

“Are you a gexi?” I asked, recalling what the young monk taught.

“Yes I am,” he smiled.

“What do you say when you meet a Gexi?” I asked, not knowing what else to say.

“You just say hello.” he laughed.

Next was an encounter with a Chinese monk and another and a young Tibetan who was a year younger than me. The Chinese monk had approached with a dinner request previously before the arrival of the Bhutanese Princess and I politely avoided his request by informing him that I wanted to see the Bhutanese Princess. “Ok, we’ll wait.” he replied. I didn’t reply as I was sure I would lose him in the crowd when the Princess arrived. When she did, I weaved in and out on the pretext of snapping pictures as the royals went around town. After walking almost a round around the ancient street, two Chinese “bodyguards” soon stepped in to stop me, demanding that I delete all footage on my camera. I complied and they then asked to see my phone. I kept my cool until they started scrolling through the photos of my phone at such an excruciatingly slow pace, I nearly snapped at them. What angered me was that they themselves seemed like Chinese tourists themselves who might have suddenly thought to take on the responsibility of enforcing the “No photo taking” rule themselves. On hindsight, I should have asked for evidence of their identities. The man was scrolling through my past month’s archive of photos, although it should already be evident to him by then that I didn’t take or record anything with my phone. “You already know there’s nothing there, why are you still looking at it?” I grabbed my phone and stormed off in anger. I didn’t know where I was going, when I turned around the corner, there was the Chinese monk.

This Chinese monk was not exactly a monk, if I understood him correctly. He had not renounced, and has been studying Buddhism at Sertar, a monastic town famous for its inhabitation of monks for three years till date. He was around my height, likely in his thirties, wore traditional yellow silk, and had a long dark red shawl around his neck that reached his kneecaps and was armed with a Chinese fan, fanning himself gracefully as he walked. I’ll refer to him as a Buddhist scholar instead. Litang was truly magical, I was certainly encountering interesting individuals here. This Buddhist scholar seemed to have stepped out of a movie set and what surprised me most was his ability to speak in prose. His speech was extremely well-refined though I wasn’t sure of his intentions. “So, dinner?” he asked again. His Tibetan friend would pick us up and bring us to a Sichuan Barbeque shop. I asked about his Tibetan friend who turned out to be a 23 year old young chap who had offered free rides and acted as a tour guide for him whom like myself, was a tourist. Interestingly, they both started off as strangers. “Is he trustworthy?” I asked disbelievingly. The Buddhist scholar replied in the positive with a Chinese idiom. I guessed what the young Tibetan was did was an act of respect and admiration and decided to agree to dinner.

At the barbeque shop, we subconsciously made vegetarian choices of mushrooms and beans. As the lady disappeared into the kitchen to barbeque our sticks of vegetarian delights, I went to the kitchen on the pretext of forgetting to inform the staff that I didn’t eat spicy when I simply wanted to check that nothing weird was going on. The auntie in the kitchen seemed genuine enough. As we ate from our barbeque sticks,I told them that I had visited a sky burial earlier that day.

Dinner, 1911 hr. Another song by ANU recommended by the young Tibetan chap.

“How did you feel about it?” the Buddhist scholar asked.

“Just..无常(Which loosely translates to imperanance)” I replied, not exactly sure how to express how I felt.

“What? You actually know what it means by impernance!” he seemed genuinely surprised. “Tell me what you mean by impermanence.”

I must have given an incorrect interpretation as he jumped in to correct me soon after. What followed was a genuinely insightful explanation which the young Tibetan chap and I listened in closely. With my layman Chinese, I could never repeat what I heard from him that evening. It was a treat to even listen to him speak. He made no mention about religion. There was no attempt at preaching. It isn’t everyday that we could meet someone who could speak so flawlessly with knowingness. Although he spoke with wisdom, somehow his thoughts and actions weren’t exactly “on par”. He asked if I have ever been to Sertar.

“I wanted to go! But foreigners aren’t allowed in.” I replied.

“We once smuggled a foreigner in.” he said. “Got him to wear sunglasses, mask and a hat”

“Foreigners have high nose bridges though, it would have been easy to tell.” I replied in disbelief.

“Tibetans have high nose bridges too.” he turned to his Tibetan friend who said nothing. “You look Chinese, it should be fine.” he said, turning back to me.

“They’ll check for identity cards at the checkpoints. I don’t have one.” I said.

“I have a plan for that.” he said.

I wasn’t so sure about that, I was incredibly tempted to go but I knew I would have problems finding accommodation with a passport and I feared ending up having to stay with him if I couldn’t get a place. I didn’t doubt the genuinity of his offer but knew I won’t feel right stepping on grounds which I should not be on. I simply told him I couldn’t risk getting deported and in case I got found out, he would be in trouble too. He said nothing more after that.

I got back to the hostel after 2000. My stylish room mate was still live streaming. She read out the comments her followers left her and sang into her phone for them – boy she really could sing and I enjoyed a whole hour of songs, thinking I must be next to a Chinese online star whose fans could only watch her performance on screen. At 2200, she packed up and I packed my bags for my departure to Yading the next day in the quiet of the room.

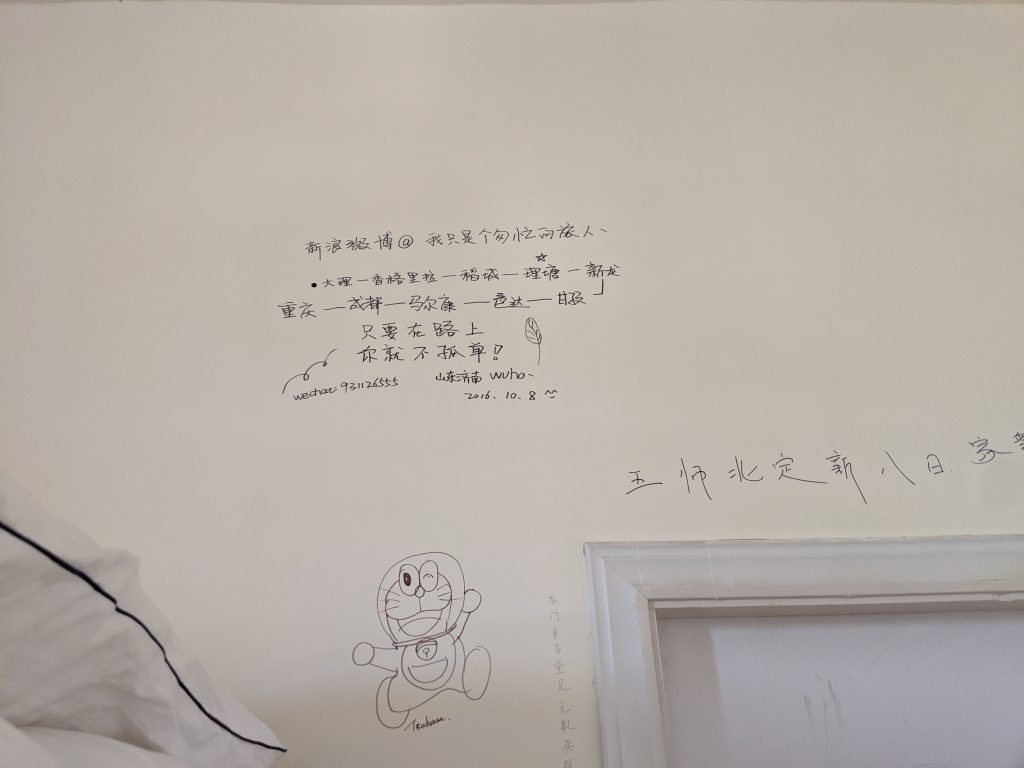

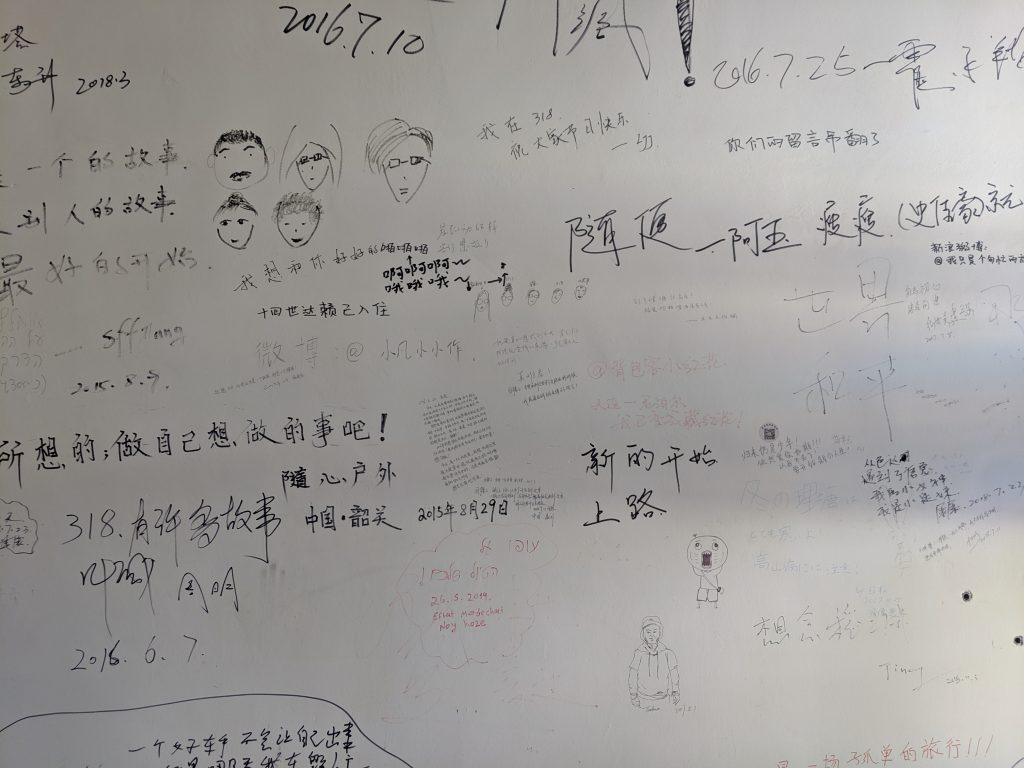

Wall scribbles on the hostel walls.

22 June 2019.

A small white dog stared at me from the bunk bed opposite when I woke up the next morning. It was curled up against its owner who was fast asleep after returning to the dormitory way past midnight. First time I saw anyone bringing a dog along with her for her travels. The dog made no sound, its tongue simply hanging from its mouth as it watched me get ready for the morning. My plan was to visit the Eastern gate of Litang first before calling the bus station to check if there were any seats left for me. The Eastern gate was half an hour’s walk away from the hostel and I stopped for breakfast at a nearby shop along the way. I asked for a basket (一龙) pau and surprisingly, the lady boss replied that it would be too much for me to finish and advised me to take half basket instead. I appreciated her honesty for she was right.

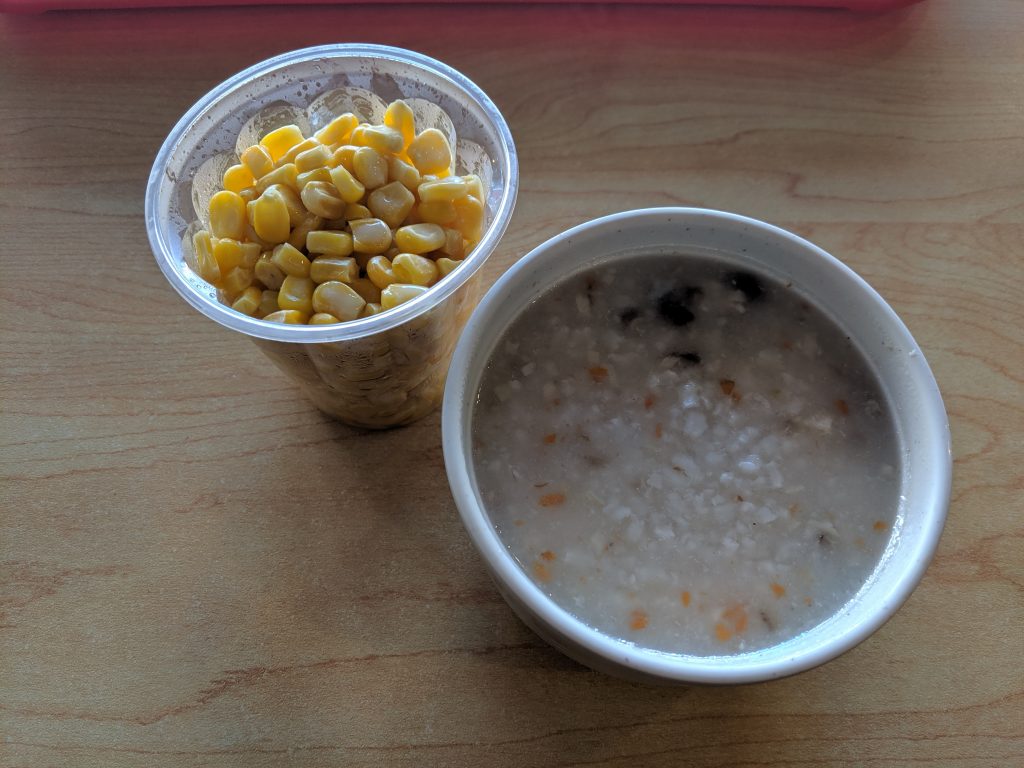

Breakfast near the hostel at 0832 hr.

Easten Gate of Litang. 0906 hr.

After hanging around Litang’s eastern gate for some time, I called the bus station to confirm my seat. Thankfully, she replied that there was one seat on the bus coming from Kangding which will stop in Litang at 1200. I immediately made the trip back to my hostel to pack.

As I waited for the bus at the station, I made arrangements for my accommodation at Yading. From what the Israeli and the Beijing roommate shared with me the other day, I should be looking to stay at either Yading Village or Shangrila Town. I called up a hostel I found on CTrip in Yading Village who informed me that the village was in the Nature Reserves itself which will close by the evening and my bus will not make it in time. That left me with Shangrila Town which had tens of affordable hostel listings and I reserved a bed at one of them. The bus rolled in at 1230 and I approached it, only to find that most passengers had alighted for lunch. The bus driver was not around so I lugged my backpack up onto the bus, thinking I will find my seat first before leaving my backpack in the luggage compartment at the bottom of the bus when the driver returns to unlock the compartment.

I couldn’t find my seat though. The seat number indicated on my ticket was occupied by a sleeping man. Before I said anything, I realized the bus licence number on my ticket did not match the one of the bus. I went back down to the ticketing office and the lady replied that the bus was the same, there’s only one bus to Yading passing through Litang. The problem was, I no longer have a valid excuse to claim that the allocated seat on my ticket was mine. Back on the bus, I sat on a seat which seemed empty as most seats had some bottles or snacks on them. Soon, two passengers came up to the bus to retrieve their stuff and claimed I was sitting on their seats. I apologised and moved to the back of the bus, thinking the last seat must be there. Another guy came up and said nothing till I asked if the back row seats were taken. He nodded and pointed to a seat further in front, claiming that that seat is empty. I wasn’t at that seat for long before I realised I was in someone’s seat again.

“Hey, leave your backpack here with me.” a lady called from behind. She had seen me move from one seat to another and guessed what was happening. “Just sit here first, you can ask the bus driver where your seat is when he returns.” she offered.

Tired from all the moving, I was so glad to hear her voice. She went the extra mile by explaining to the surrounding passengers my situation who have started to return from lunch. No one seems to know about the extra seat the bus ticketing lady had promised me. The bus driver returned and I showed him my ticket but he also had no idea where that empty seat was. I eventually found it by asking if anyone had an empty seat beside them loudly in front of the bus passengers. Forty eyes stared back at me for a brief moment before someone replied. At last, I could stay at a seat for the next few hours to Yading. The lady who had voiced out for me turned out to be from Hong Kong and was also travelling solo. She was an avid traveller, spoke fluent Chinese and married a Mainland Chinese whom she met in Tibet sometime back. By luck, she would later become my roommate for my time in Yading.

Arrival at the Hostel in Yading. 1748 hr.

Dinner. 1935 hr.